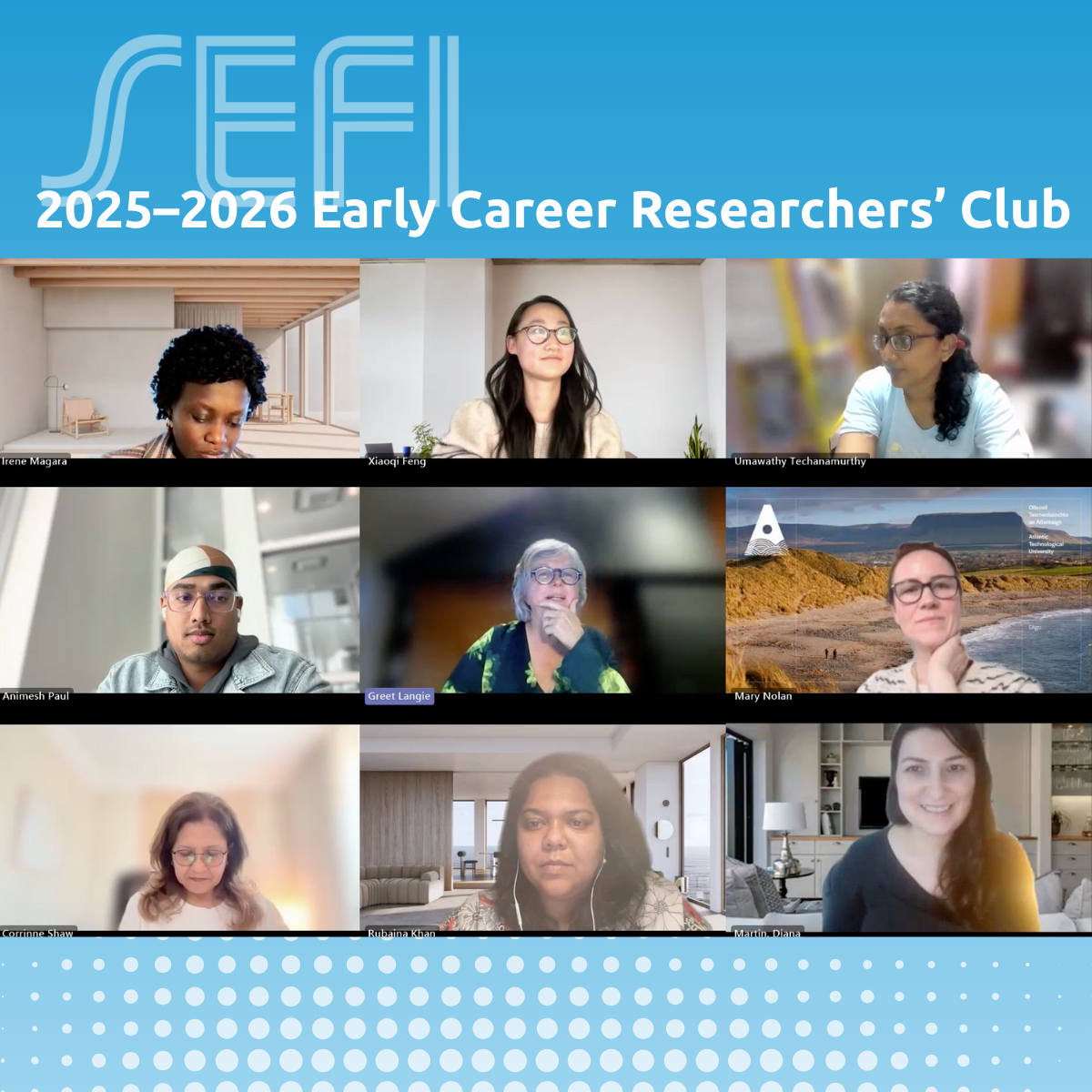

The SEFI Early Career Researchers’ Club is a 9-month initiative designed to support and connect…

It seems so obvious that it’s hardly worth commenting on – the reason we exist as a field of Engineering Education Research is for the improvement of engineering education, for promoting change. In many parts of the world, we receive taxpayer money to do our research, and we have found a home in universities keen to benefit from this work. We write preambles to our papers about our commitment to cracking problems that have thus far eluded the field, such a significantly broadening participation in engineering programs, and closing the gap in achievement between students from different social backgrounds.

In this short piece, I do not plan to say that we should not be focused on the quest towards (positive) change in engineering education. However, I do think we should apply our scholarly minds to thinking a bit more deeply about how change happens and does not happen in (engineering) education. Simply advocating causes and banging on a drum does not justify a research field – a couple of enthusiastic Deans and industrialists could do this well and most probably already do. But we will need to shift our research culture a bit if we want to sincerely think about how change happens – and why we see the often intractable patterns we do, as well as dramatic and sometimes underappreciated real change.

Education is a cultural enterprise. As science and engineering professionals we understandably tend to focus on technological innovation, and we are easily taken up by seductive arguments that technology can effect the social changes we desire. Yet, causal relations in education tend to be more complex and culturally situated. And in the hyper-marketized and stratified university systems we now inhabit it’s often hard to see what is really happening beyond slick branding and reputational surveys.

I’m interested in real evidence of change. I was privileged to live through a dramatic positive political change in my country when I was a young adult, and this has left me with a sharp sense of questioning and a reluctance to take anything at face value, along with an underlying optimism that things you never thought could change, actually can. But often the forces that really effect change will be bigger than you and me – like hapless sailors afloat on a stormy sea we can work hard to bail out water and tighten the riggings, but we can’t change the size of the waves. I don’t mind the modest localized work of keeping things afloat – and sometimes the rare opportunity to design a better boat! Here’s to research that goes beyond the usual rhetoric and drills down to what is really impactful on the ground – for students, faculty, and employers.

For an approach to thinking about causal mechanisms in engineering education, I recently wrote this article with my colleague Dr. Margaret Blackie from Rhodes University, published in the inaugural issue of the Southern Journal for Engineering Education: https://sjee.org.za/ojs/index.php/sjee/article/view/11

For a totally different read which in a way is a case study of radical change in one university department – see this book overviewing the first century of the Department of Chemical Engineering at the University of Cape Town: https://openbooks.uct.ac.za/uct/catalog/book/33

For a more academic write-up and analysis of this change, see this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1045479