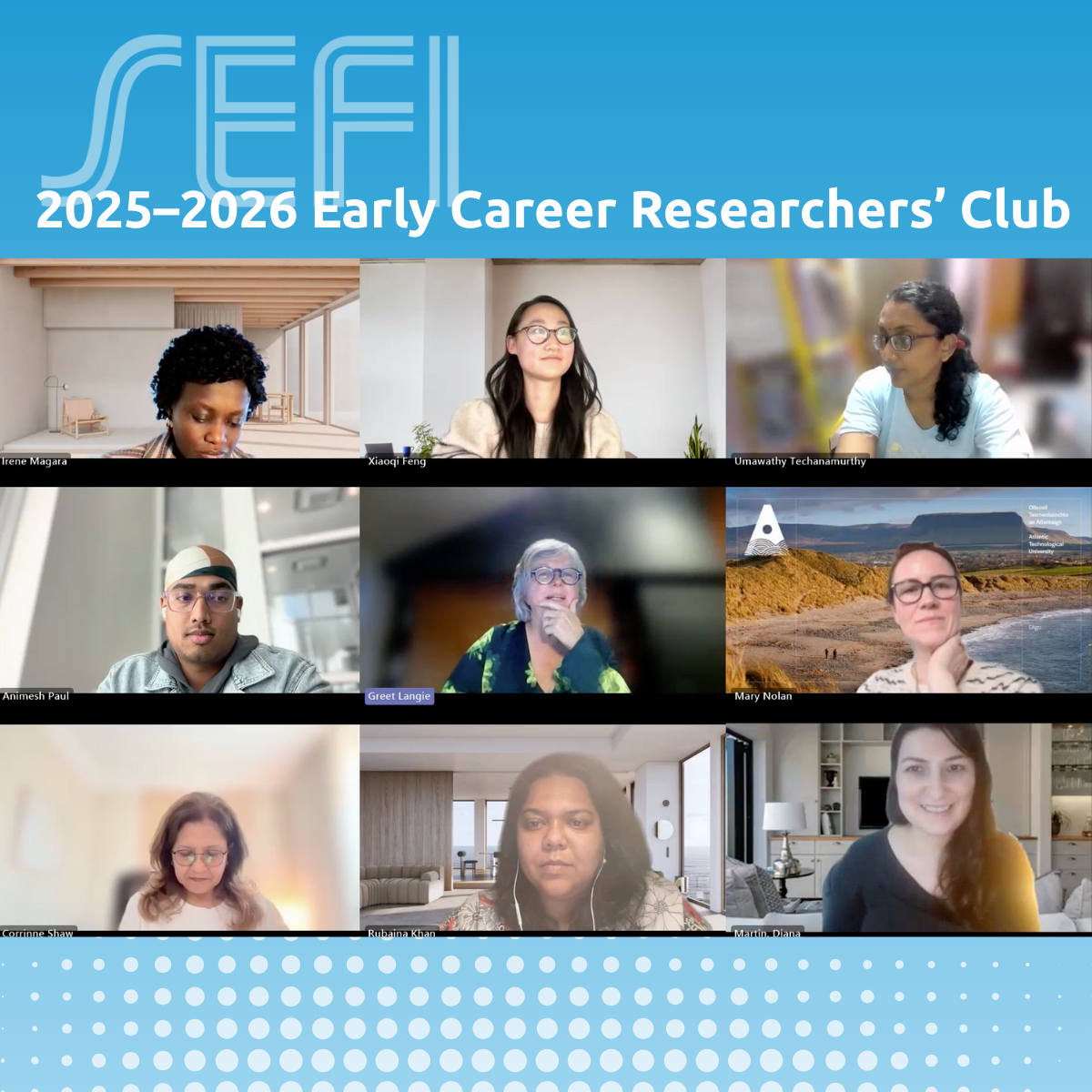

The SEFI Early Career Researchers’ Club is a 9-month initiative designed to support and connect…

Natalie Wint, Swansea University, The UK

For the last two years I have been teaching a module which involves sustainable, human centered design work. The reaction of students to the course has been variable but is generally consistent with the reported “culture of disengagement” (Cech, 2014) and lack of social responsibility (Canney & Bielefeldt, 2016) present within engineering education.

In the first year of teaching, I was upset by the sarcastic comments, the looks of disinterest. But as well as upset, I was critical of my students and their attitudes. Reading literature that focused on the nature of social-technical dualisms (Faulkner, 2000; 2007), intermingled with the hurt, shame, and disappointment associated with negative student feedback had left me making assumptions about the reasons students seemed disengaged. I had assumed that they were primarily disinterested in issues of sustainability and social justice, and in some ways, I had started to blame them for the apparent choice they had made.

In the second year, I was more critical of myself. There were increasing reports, articles, and surveys (e.g., National Union of Students, Sustainability Skills Survey) informing me of the increasing number of students wanting to learn more about sustainable development and demanding their institutions to contribute more toward the sustainable development and goals (SDGs). Students were telling me that they had chosen to study engineering to help people, to contribute towards the issue of climate change. So, why was I not able to arouse enthusiasm from students when teaching something that they claimed to have wanted? Was I really that bad a teacher? I started reading students’ feedback in more detail, the comments they left on discussion boards, their reactions to reading assignments. I began to detect a sense of disempowerment. Students appeared to be conflicted in their desires to act in a sustainable manner, and their need for an income upon graduation, whether that be with a company who shared their values or not. They seemed powerless to help communities in the countries thousands of miles away, around which the design challenges were focused. Such feelings are perhaps made evident by the comments made by a student, shown below:

The whole looking inside yourself, responsible engineering talks are preaching to the converted, we all know what we can and can’t do at this point, and when it concerns the environment and climate change. University students are all too aware of the risks of climate change considering that we’ll be the generation that has to deal with the consequences of the previous generations’ inactions

To me this voice sounded angry, it appeared to be laying blame. I began to feel guilty, like I had failed them. I had been blaming students who had been educated in a system in which they were taught to place technical knowledge at the top of the knowledge hierarchy and to prioritise STEM above other disciplines. I had been stressing the importance of social responsibility to students, without giving them the tools and confidence to act in a socially responsible manner. As Pawley (2019) points out, as educators, most of us “indoctrinate students into neoliberalism” and fail to make students aware of alternative modes of thought which may allow them to “conceive a way of being outside this neoliberal worldview”.

I began to realise that teaching students about sustainability involves much more than content. It involves confronting several tensions, many of which are influenced by marketisation of higher education (HE) and the ways in which neoliberalism pervade engineering education. We must answer questions about how we balance our responsibility to produce employable graduates, with the responsibility to ensure that students are free to explore themselves, their beliefs, and motivations in a system which values their academic success. We must understand how best to introduce students, who have been socialized within a discipline which values rigor, objectivity, positivism, and reductionism (Riley, 2008), to different forms of knowledge. We must start to overcome the culture of competition and ensure that students are able to fully benefit from working with those who have different experiences and perspectives to their own. We must develop ways to empower students so that they feel able to enact meaningful change within a culture which acts to discourage alternative modes of thought. Perhaps most importantly, we must consider the extent to which we, as educators, should try and address these issues. For example, Shor and Freire (1987) described the way in which student resistance to liberative pedagogies was rooted in job anxiety and Freire (1970) argues for the need to prepare students for the current (neoliberal, capitalist) state of the world.

Answering these questions is non-trivial and involves making choices which may affect the way in which we, as engineering educators, are perceived by students, colleagues, and management. Teaching sustainability involves building trust, being empathic, and treating students as allies and can leave us feeling vulnerable and exposed. How we do this whilst keeping our emotions intact then becomes another question.