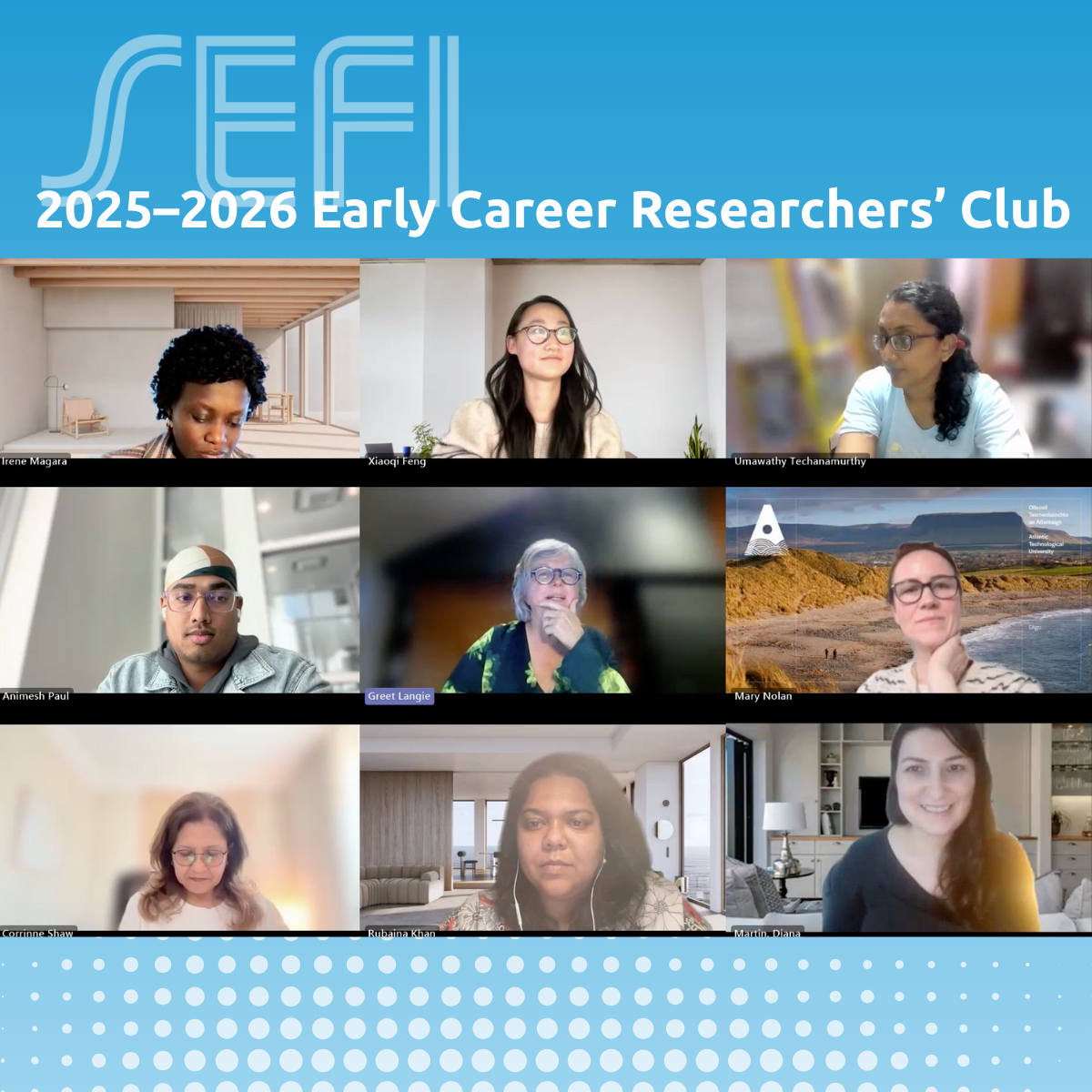

The SEFI Early Career Researchers’ Club is a 9-month initiative designed to support and connect…

As engineering educators, we are providing guidance for students about how to learn, what to learn and how to understand their learning so as to continue to develop these skills over their lifetime.

As engineers we have the moral imperative of sustainable practice, of doing no harm on a long term scale. We cannot teach this unless we come to our work with a firm footing in the landscape we know and love, and a story in our head of our purpose. A story that grows as we work on projects in our discipline, as we understand the complexity of the systems we work with and that retains a basic narrative, embellished with new locations and experiences, that are tied together to retain the complexity of systems thinking.

Being in Australia, our engineering can draw on the oldest technology such as axes: involving flinting, resins and twine; fish traps: involving tides and river flows, dry stone walls, weaving nets and temporary bamboo dams; eel traps: including surveying technique to design for slow runoff and smoking of eels for trade; mining of ochre: including maintaining trade routes and excavation tools; all of which were done sustainably.

These processes were taught in oral narratives that have much in common with modern knowledge sharing. This approach to knowledge sharing resembles the teaching required to learn how to use an old machine at your workplace. When the operator is retiring, they will show you how it functions, but each lesson will be different relating to the circumstances of the use of the machine that day. So, the Tacit Knowledge sharing about the management of country is done through stories that are retold over time to match the particular circumstance (la Niña, el Niño) of that period.

Aboriginal people only share stories to a certain depth with certain people. When a child, or new to Aboriginal society, we are told the moral stories, the dreamtime stories at a child’s level. Then as a child reaches youth, we are told about the context in which the moral story occurs, the environment where we need to survive. As an adult people are told the relationship of this knowledge to the broader community interactions. Only when a person is grown and has responsibility for a specialisation will they be told the deep knowledge of that totem animal, plant, place or part of the environment. The last stage is the spiritual knowledge, the knowledge so deep it takes a lifetime to learn (Sveiby & Skuthorpe, 2006). Similarly we publish our academic work on engineering through journals selected to reach only our peers.

This narrative, the dreamtime story, is about aspects of the environment that are true in the past, present and future, they are the patterns of the world around us. This knowledge is stored in stories to assist the knowledge sharer to remember the features of the story they need to impart. When they see a particular rock or pool they will talk about that area, and these features help the listener to remember. Stories are thus tightly bound to country, the land where they apply.

So to our engineering stories, what processes and risk avoidance we need to take, are bound to the working context in which we use this knowledge, and must be taught within these contexts to have meaning and to be memorable. Also we need to make the story part of our student’s life. We should start with a moral imperative to our practice as Aboriginal stories do. It is the ethical considerations that are at the root or any lesson: to make the world better (our design processes); to understand we see things differently in different contexts (basis of quantum mechanics); to base our knowledge in our prior learning (used in biomimicry).

Instead of astounding our students with the wonder and marvel of the world they have had little experience of, we should start them on a firm footing. What is the landscape they know well, what are the values of their culture, what are their own contradictions, so they can accept these to occur in other people? From there they can reach out and engage with new knowledge. What is the moral of our domain, and how can we put that into a simple example for students to enter the world of our discipline?

Reference

Storylines https://storylines.com.au/