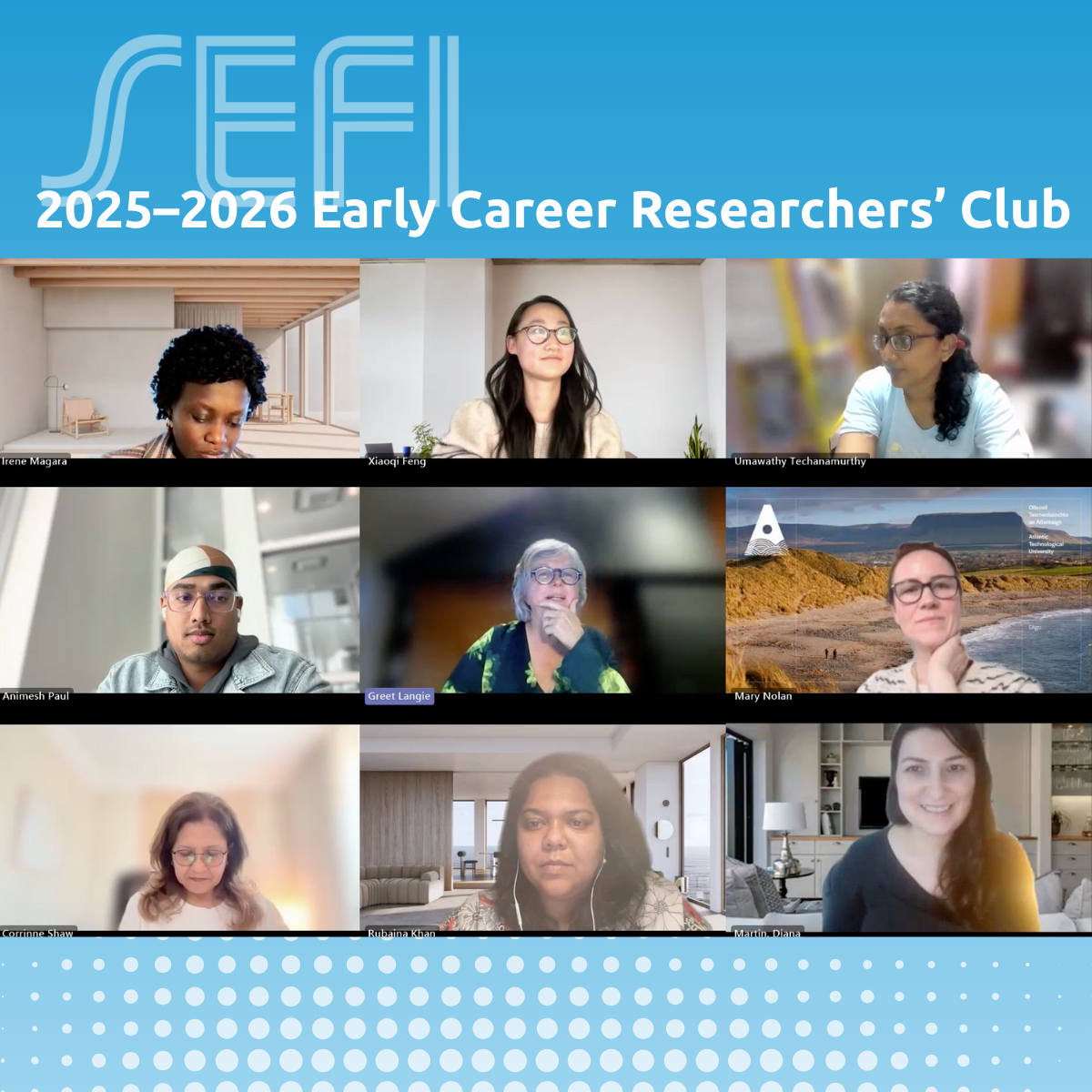

The SEFI Early Career Researchers’ Club is a 9-month initiative designed to support and connect…

Mason University, USA

I recently designed and implemented online role-play case studies in an undergraduate ethics course. I make students accountable to a person or a committee who has to act on the advice they receive. I found that through this exercise students develop situated insights and diverse perspectives; I discuss some other strengths and challenges of online roleplay in engineering ethics education.

What does role-play bring to the table that a simple case study does not? Role-plays allow students to take on different perspectives by enacting specific roles. Do to do justice to their roles, they have to develop a situated insight into the scenario they are given. They might disagree with the perspective they have to adopt and this shapes their thinking through cognitive dissonance. Even when they agree, debating an issue with others makes them think in a new way. In my role-plays I make students accountable to a person or a committee who has to act on the advice they receive. This puts additional onus on them to have a productive discussion with an outcome that is outcome-oriented.

Of course, not every discussion goes as planned or can be categorized as a deep learning experience for the student. This is no different than any other pedagogical intervention. The differences arise depending on the composition of the group, the interest students have in the case content, and the simple logistics of how the discussion proceeds. Irrespective of these uncontrollable factors, there are some provisions I make to ensure a better learning experience. I use more than one role-play discussion in my course, currently four, and I have seen these to be more effective as students get a chance to “warm-up”; learn what the pedagogical tools entails. I have also found it helps to keep the group composition the same as this allows students to develop a rapport. This is especially the case if they don’t know each other from before.

Finally, I have learned about online teaching through the implementation of role-plays. Although my initial plan was to use the role-plays in face-to-face instruction, the pandemic forced me to improvise as classes moved fully online. I embraced this opportunity as I knew from my prior research that online interaction, if implemented correctly, provides affordances that are unique. In particular, I saw the ability to use video or audio for role-play discussions as a positive development. I opted to give students the choice whether to turn on their video during the discussion. I did this to be fair – I knew that students have different bandwidth limitations and also varied in their comfort level with video. I also knew that many students are less stressed and anxious when not on video and I have found that giving a choice and letting students select has enriched the discussion. Since no one is anonymous in the class, the downside of someone hiding behind a pseudonym and being overly negative is avoided. Overall, the lesson for me is that ethics is not just about what we teach, the content we design, but also about how we do our teaching.

Acknowledgments: This research is joint work with Ashish Hingle, Huzefa Rangwala, and Alex Monea, partly supported by U.S. National Science Foundation Award#1937950. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.