We are excited to announce that registrations for the 53rd SEFI Annual Conference are now…

Why are we here? Comparing medical and engineering ethics

By Iain Skinner & Adrienne Torda, University of New South Wales (Australia)

Medicine’s Hippocratic oath is arguably the most famous code of professional ethics. Engineering does not have anything like it. Maybe, then, there is something to learn by comparing the features of professional ethics in both medicine & engineering, and the way the disciplines approach education of respective student cohorts.

First disclaimers: What follows is based on our own experience, although anecdotally confirmed by colleagues elsewhere. Also, professional conduct—respecting people, protecting confidentiality, etc.—is similar in both professions, so will not be discussed.

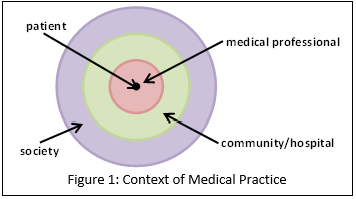

A more interesting comparison comes from the question of accountability. To whom and for what is a medical professional accountable? Obviously to the patient (or patient’s agent) and for the welfare of, first, the patient and, then, society.

A more interesting comparison comes from the question of accountability. To whom and for what is a medical professional accountable? Obviously to the patient (or patient’s agent) and for the welfare of, first, the patient and, then, society.

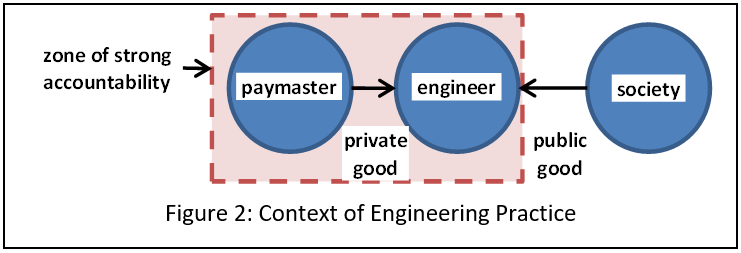

But to whom is an engineer accountable? To the pay-master (employer, client, etc.)? Or also to the wider community affected by the engineer’s work?  Yes, there is an ethical obligation to the latter group. This tension is at the centre of engineering. Immediate accountability to the pay-master may conflict with that broader accountability; desired benefits for the pay-master may compete against broader obligations and costs. Rarely in engineering are costs and benefits equally distributed. This is the conflict surely felt by engineers at Takata and Boeing.

Yes, there is an ethical obligation to the latter group. This tension is at the centre of engineering. Immediate accountability to the pay-master may conflict with that broader accountability; desired benefits for the pay-master may compete against broader obligations and costs. Rarely in engineering are costs and benefits equally distributed. This is the conflict surely felt by engineers at Takata and Boeing.

Recent medical innovations have opened some similar ambiguities. For example, the cost of privatised health care have exploded and emphasised a double standard for the healthcare of those with limited resources.

When comparing education of medical and engineering students, the settings are very different. Ethics teaching is much more structured and explicit in medicine. This is needful because, from an early stage, students deal with real patients (i.e. their industry experience). In meeting an immediate technical challenge, an engineer can easily forget societal impacts. A patient is much harder to ignore. The engineering student’s industry experience comes later. They won’t meet patients. Rather, in the workplace they will be expected to address the interests of their employer. Whether they will consider the interests of society is unpredictable and not explicitly assessed. Perhaps it should be. Without such a strong tradition behind it, engineering’s role models in the work-place may not be the best at demonstrating ethics or social accountability.

There is much work to do in preparing the next generation of engineers. It may need a structural change to their education.

This is based on a paper entitled “Developing awareness of stakeholders: Contrasting professional ethics education in engineering and medicine”, presented to the Australasian Association of Engineering Education Conference, Hamilton New Zealand, 9.-16th December 2018.